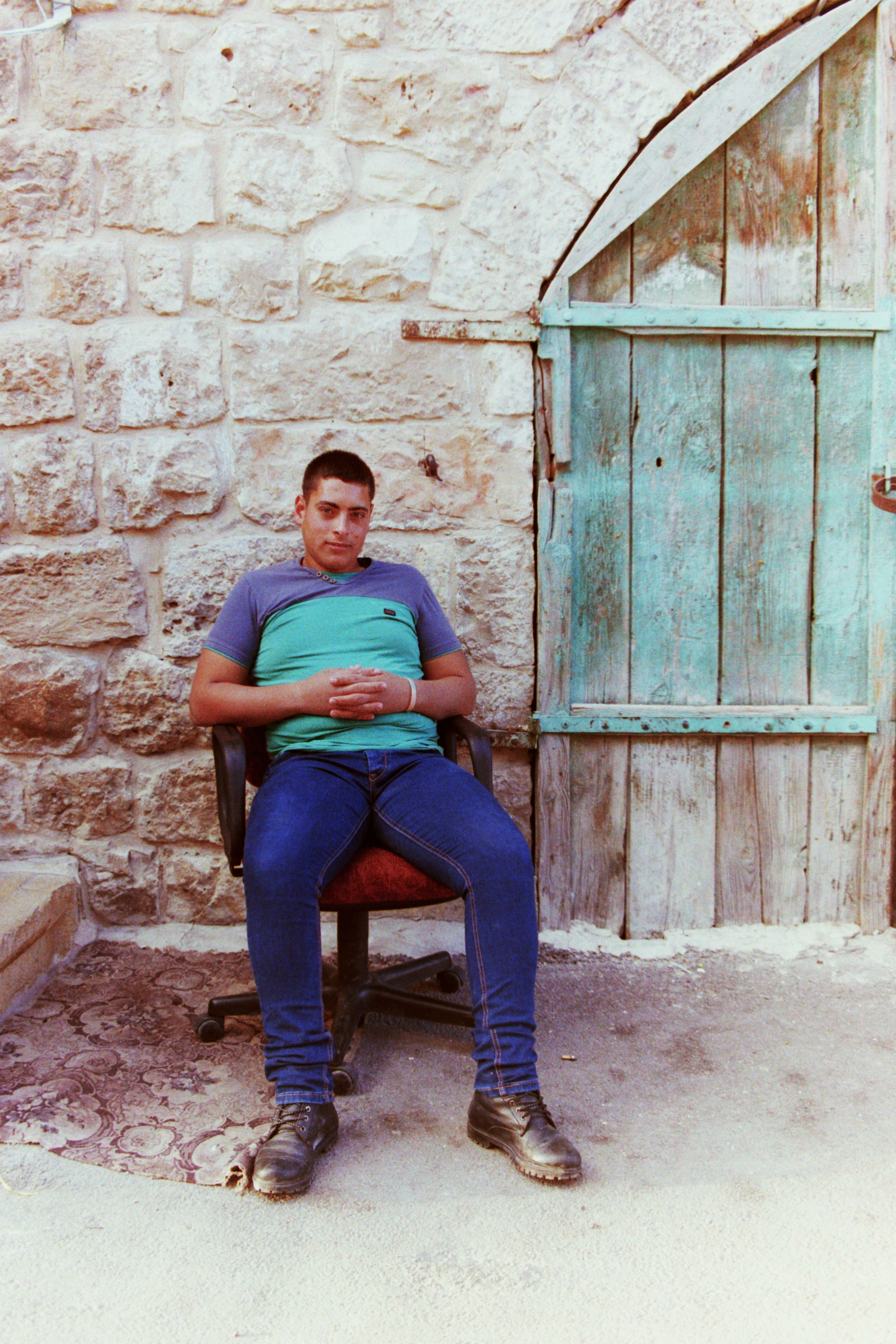

Separating two worlds, the old and new, the staircase one last time is mounted by Richard Louis, walking into his retirement. The old man feels it in his legs, the staircase rescinding his weight; and upon taking that last step sees his son, who is waiting for him; the chiseled face, which has not changed since childhood gazes upon his in admiration. Two men, having met, shake hands. A father and a son, in total peacefulness; and yet, there is apprehension. For the old man, Richard Louis, is retired, having left that workplace. In the mouth of the subway, they’ve met; and they are granted a look at one another, a opaque glance, which transports them back to steadier times and when times looked less drab. A time of uniting is the moment, at present; upon shaking hands, they exchange greetings in simple words, which mean little beside the grand features by which they’ve known each other for so long. A father and son. In harmony.

Greetings.

Goodbyes.

The couth undertone of winter is imminent; they feel each other’s body heat through their thick coats and take a step synchronized in a direction, which feels irregular; an anomaly has descended: the warmth, cushioned by sharp winds and the cracking cold, which sets them heavily Earthed. A sprouting or V-shaped branch is a way they feel, like a moose, with its heavy head pulling him towards water and nutrients. Today is a day for celebration, because the old man has retired, a splendid bout of upwards of sixty years working in the City, as an architect. The young man has wished he followed in his footsteps; and yet, the content young man, the son of Richard Louis, takes lead in the short-lived moment of lucidity, which preludes the starting of a motor. The child and father relation has been mediocre at best, with the frill edges of temperament coaxing an otherwise stellar relationship.

The temperament has been roused by years of unnecessary council; because father knows best, son is always at a loss, at a loss for words, at a loss for emotions; and yet, by the finality of everything, there is a pot of gold, savings having been stored away, like a bear steals away meats and fish into his gut, in this season, and then caves in for hibernation.

It’s purely instinctual. A bear recedes into its den as a man does his bar, on a day such as this, says the son of Richard Louis. A day like this is a day one celebrates. It seems the tables have turned, by means of a daring poltergeist—the son advising the old man and cajoling him out for a night on the town, which is filled with beer and wine and tasty bowls of snacks and women and youth. It’s all right, says Richard Louis. I’ve had enough for one day, he says; but as the car starts and pulls out from its parking space, which is beside a curb and a parking meter, the son forgets his manners, doesn’t bite his tongue and says, We’re going out tonight.

It’s a business casual place. You’re dressed well as it is. We’ll make a stop by my place, so that I can get dressed.

Business, thinks the old man, is at an end. With this publicized deficiency of openings for jobs and the growing demand for foodstuffs and disability checks it’s a wonder I’m retiring at sixty-five. He questions himself, feeling older than he is, sixty-five?

The mind crosses morbidly into inheritance and paperwork. Richard Louis is composing his will, in mind—the ethereal place where thoughts can happen on their own accord or on a whim, like a twig falling to the Earth, indenting the snow. The light impression given by the notion is none too far from disconcerting. There is the house, the car, the savings, the valuables—watches, rings, and jewelry. There are the books. The countless books, which compile Richard Louis’s library—the high bookshelves filled with novelists like Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Jules Verne. Richard Louis almost brings it up, his son’s inheritance, but drops like a rusty penny in a fountain the topic. They are approaching his son’s home, a modest two story home, with a green rooftop coated white by snow.

Richard Louis has always enjoyed that rooftop. It is a vibrant green, not the standard forest green, but a lime green, like the leaves of a young oak tree. Yellow-green.

Two men, separated by the ghostly apparatus that clinks and toils when it changes gears, remove themselves from the car. Approaching the house, the silver ground crackles under their feet. Crisp breaths are taken through the old man’s nose; and he is sharpened by the bite of the season. It’s a pleasant bite, like the bite of a teething puppy dog.

Musing, the old man thinks, Glad I never got one, referring to dogs. A twig must have fallen. Because of the nostalgic day, the end of workdays, inheritance comes to mind, once more; but it seems his son has inherited all that is of value, already, the musing Richard Louis thinks, thinking of the personality.

His son seems to be doing well, he always had a good head, but he can remember a few times it got the best of him. Richard Louis eddies away from the thought.

The décor of the household is quite nice—maroon drapery, white carpets—and the old man is offered a drink upon entering the house, to which he declines the offer, he’s not thirsty.

There are so many similarities between father and son, the high cheekbones for one, the eagle-like nose, and brown eyes, the careful arches of their eyebrows and big ears. The creases at the corners of their eyes, of which Richard Louis has more, that sets them apart. That and their intrinsic views on the world. Richard Louis has been okay with his small house—a single story house, with two bedrooms and one bathroom, a small modest white kitchen, with a homey little living area separating the bedrooms and the kitchen. He decides to step outside, into the frosty outdoors. The street is quaint. The lawn, underneath all that snow, must be manicured.

The fence is taught. The trees lining the street stand like men in a queue at the soup kitchen.

He can almost see them exhaling their oxygen; and he takes a breath, admires his breath. It’s much like a cycle. One gives, one receives. Only it’s better to be on the receiving end.

On top of all the years past, Richard Louis has retained class. Receiving many a joyous night with candor is like a cup of warm milk to put him to sleep; he relishes his memories before bedtime and those memories lull him into sleepiness, which he values much like a bear values a river full of salmon; they swipe in with their claws and withdraw their meal. Really, the only topic that doesn’t lull Richard Louis into his sleepiness is the thought of his wife; he is a widower as of late. His wife has died five years past and he can still remember the texture of her stockings, the way she washed herself in the evenings and smells like soap in bed, the way her softness takes him, propels him into the armpits like a hound in a foxes den.

There is a fireplace in their old house. The chimney reaches up to the rooftops and expels white smoke. Richard Louis’s son asks how Santa Claus fits in the chimney, how does he get all the way down? The answer is one word—Magic. Escaping the lips of an equally mesmerized father the word sounds like a magical cue, which renders the young boy into reverie; and awe takes prescience. The boy sleeps with the image of cookies and milk set out for the fat man, who shimmies down the chimney once a year on the twenty-fifth of December. Every year, it happens and the young son is truly hypnotized by the notion—the North Pole, the elves, the fat man, who rides a sleigh around the world in only a few hours, he must be a superhero.

Now, the notions are few and far between. The young boy has grown and learned that it is a myth; but something in the daring young man has him thinking that myths have a source of realism. They have emanated from somewhere, inspired by a partial-truth, a quasi-reality, which adorns the minds of the old and young. This is the way the imaginative mind is composed.

Now, the poles have him curious to a different effect. It’s the polar shift, which enamors the young man with riveting thoughts and conversation at the evening celebration. The conversation is one of natural disasters and the polar shift. Russia will be in the States as Europe will be in the Pacific. The climates will have exchanged places, like body heat in a cold-blooded animal.

Age, however, doesn’t change places. It’s a steady stream of consciousness. It goes in a straight line, or a circular trend, cyclical, if one believes in that circle of life hogwash or the completion. Richard Louis deviates from the conversation, his thoughts touching back on soot and Santa Claus and the holiday season. Even the sun feels cold on a day like this; he doesn’t feel its warmth in the afternoon, it’s cold and electric. He feels a comparable aspect to his own son, in this case. The young man has effectively left the old man out of the conversation; however, not intentionally, just as the sun on a winter day doesn’t intend to be cold. He is feeling less and less welcome.

All the man wants is to exchange a good word and return home a retired man, and relax as does a retired man. Moreover, what is well to be exchanged are the rudiments. The rudiments with the refined. The bum with the classy, thinks Richard Louis, self-depreciatively. A token evening is one part of the grand scheme. What really on this night is the young man doing with his father? It seems it is a token, like one receives at an arcade. One deposits a token into the machine and there is a time of entertainment. The game carries on and eventually ends.

Recalled is the handshake upon entering this restaurant. Richard Louis has shaken hands with a man, solid in his frame, with a firm handshake, broad shoulders and done-up hair; and it's like his handprint has been scanned, like a Morphotank in a jail, the impression never-ceasing, the handprint never failing to bronze up any impression given by the old man. He has reached his Golden years, in a machine state.

Talismans, brass rings, shoe polish retain most of the human being today. Richard Louis feels his gut has become brazen in the circumstances; his shoes have become too small, the toes may burst out the fronts like a clown’s. Somebody says something, but it goes unheard. It is directed towards him; and he flinches, snorts in agreement.

Maybe he’ll write a book in retirement. Pages on pages of narrative and prose to go along with the mundane happenings of old age; but is it so mundane? The sharp air of winter keeping the lungs alive, the lucky sun in the height of the afternoon, a whiff of acrid smoke in the City. All keeps ends on edge.

This must be a means to end. It must be. Retirement, this evening.

Without a word, Richard Louis steps towards the restroom. He moves to a closer point, attempting in this scenario to learn who he is. From his reflection he is mere inches. Perhaps it’s best to reconcile himself before venturing into his son’s heart. It is almost time to go, when he returns to the table and finds himself wanting to trade jackets with his son.

Similarities are what he finds in the two jackets. But if he suggests this they might think of him as a zealot.

They’ve gone on their pilgrimage into the City, visited in original attire the setting of old and new, old and young, brought together, like a museum and its visitors. Satisfied is Richard Louis, but taking the boy on a tour through his memories is what he really wants. To coast through panes of glass and windows and lenses so that he can view how he, Richard Louis, really thinks. But there is the tied down effect, the part where his son knows all and what really can the old man teach him at this point? Something about desire.

There is a hill down which they navigate on the way to subway station and back to the City minor. Richard Louis pretends he has gone skiing—he never has—but he is good at it, innately; he races down the hill on skis, like a boy who has found a free bite of chocolate. The City is melting in his vision. And slowly they descend into the subway station, spelunking, or otherwise zipping through the cave-like cavern, with fervent legs, feet, anticipation, skis.

Deepness is found in that subway. Deep like the ocean, or deep like the snow, or deep like an inhalation, or deep like a gulp of beer. The spicy scent of the subway takes the two, father and son, father apart, yet closer. For they are sitting beside one another, thinking of each other, unknowingly.

Retirement is like birth thinks the aging Richard Louis. It’s like he’s seen a new light and he is excited to go home, finally. His bones are chilled, all the way from the skull to the humorous, chilling, to the radius and ulna, all the way down his spinal cord, to his coccyx and femur and tibia and fibula. The metatarsals are begging for a hot shower. The metacarpals in his hands equally asking for the hot water. His son, on the other hand, is all muscles. All the way down from the trapezius, down the latissimus dorsi, to the gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus, enamored by fanaticism; but it is Richard Louis who feels out of turn. For his old bones are feeling brittle and his muscles are feeling tattered and his spirit is feeling insubstantial; and his son is walking with such sureness, smartened at the lashing cold, fastidious. Equality is all Richard Louis wants, to be equal—not young like his son, he’s been that age already, but to know what he’s thinking. He wants a piece of his mind; he wants to know how really he feels on this evening, because it is an evening of importance. However, it seems it has fallen into commonality. They split in a second, like a hairline fracture. The explosive schematics of the relationship shows all the bones, all the muscles torn apart, in the eyes of Richard Louis, it’s like he’s taken a hallucinogen. Equal men, that’s all he wants; he wants to be equal men, strong men, while they are eating food and chewing and creating energy in their brains, which is solely composed of gray matter and electricity—it must run cold.

Richard Louis has thought before how captivating the human body is. It eats and from that food creates in the brain electricity; the brain via this electricity tells the muscles to contract and move the bones in a direction, so that the body can move; it’s like magic, an incredulous organism. One eats, and then tomorrow one moves; surprised there’s not a carrot dangling before their heads, but there must be, on some electromagnetic and ethereal level of vision, there is that much irony.

The hairs on Richard Louis’s head are like tilde symbols, reaching out looking for an extension or an absolute value. Questioning his son, he says, Had a good time tonight? His tone a bit vivacious, ironic, but evidently predestinate.

He seeks to balance the equation. Calculus is not his strong suit, but it might be easier to get through to a derivative than it is his son. Genealogy and pedigree are more so the topic in question; and it does dawn on him that they are different men. Obviously. They are in two different places and the same time, it’s not like he’s a practiced Buddhist, able of being multiple places at once, banging a drum in one room while meditating in another. He removes a comb from his pocket and parts his hair. Equal men. Different men. Is there a difference? There must be, because when he thinks of himself as an equal man he feels vibrant, a shaking in his feet and arms, like he’s nervous; but he’s not. Anew is the proper way of putting it. Anew and aging. Richard Louis is longing to return to his own settlement. He skin pulls him towards the car, a diversified vessel, an instrument of motion. As opposed to stasis, like a Longhouse or a Hogan or an Igloo.

They arrive. His small house is equally yearning for Richard Louis to enter, start the fireplace, have a cup of coffee, and sit down and read. Before exiting the vehicle, Richard Louis turns to the left, shakes his son’s hand and says, See you later, which he doesn’t say with anticipation. It’s a melancholic tone of voice. He refuses to say thank you. He exits the car and faces his son through the frosty window, and then it dawns on him that this is the last time they are together as equal men.

Anders M. Svenning’s work has appeared in Forge Journal, Grey Sparrow Journal, and is up-and-coming in Bahamut Journal and The J.J. Outré Review. His motto: What is evident rarely is the case.