I love tinkering. I loved my garage. I love the fact that having tools and a space to use them opens up a world of exploration and creation. I am an old man at heart. I’m just waiting for the years to catch up to me to a point where it is appropriate to mutter to yourself all day while shuffling around in your workshop with a partially deaf dog napping in the corner and talk radio blaring in the background. I can’t wait to start needing medication so I can collect pill bottles and put things in them.

Of all the questions, I’m most interested in how. A normal person sees a table and says, hmm that’s a table. I see a table and I immediately wonder how the legs are attached. Will that be a sturdy fitting over time? I go to a barn wedding and I’m checking out the barn. Give me a cocktail or two and I’ll climb up to the loft to inspect the joinery. I’ve done it before and I’ll do it again. You can’t stop me.

I spent the last six months searching the Internet multiple times a day for an antique tool you’ve never heard of called a power hammer. A power hammer is a machine that lets you work bigger material faster than you could ever work by hand. Its like having a whole bunch of friends that are also blacksmiths helping you hammer hot metal together. Look them up on the YouTube, they’re sick. They were made 100 years ago and only about 5,000 of the particular style I was looking for still exist. When they pop up, they usually sell within a day. Faster sometimes.

The perfect one came up on Craigslist one morning, and I didn’t find it until 11 p.m. the day it was posted. I had broken my routine of searching every morning because it was a weekend, and I cursed myself for it. I had anxiety stomach all night and couldn’t sleep. I was like this kid I saw on the Internet one time when his family deleted his World of Warcraft account. I was making jerking motions and speaking in half sentences and making popping noises. I got up a 4 a.m. and began researching the best way to transport this 1,000-pound machine from Delaware, in case it hadn’t sold yet.

I got the guy on the phone around 9:30 a.m. and literally (and I’m using literally to mean literally here) begged this total stranger to hold onto the machine until that evening when I could get there with a trailer. It was pathetic but it worked. And I’m not even telling you the whole story. I hope one day I will know the joy that comes with being a father, but until then, the memory of taking possession of this little fellah will do. I show pictures of my power hammer to total strangers. They don’t care at all but I keep showing them. I can’t help it. I’m so proud of the little guy.

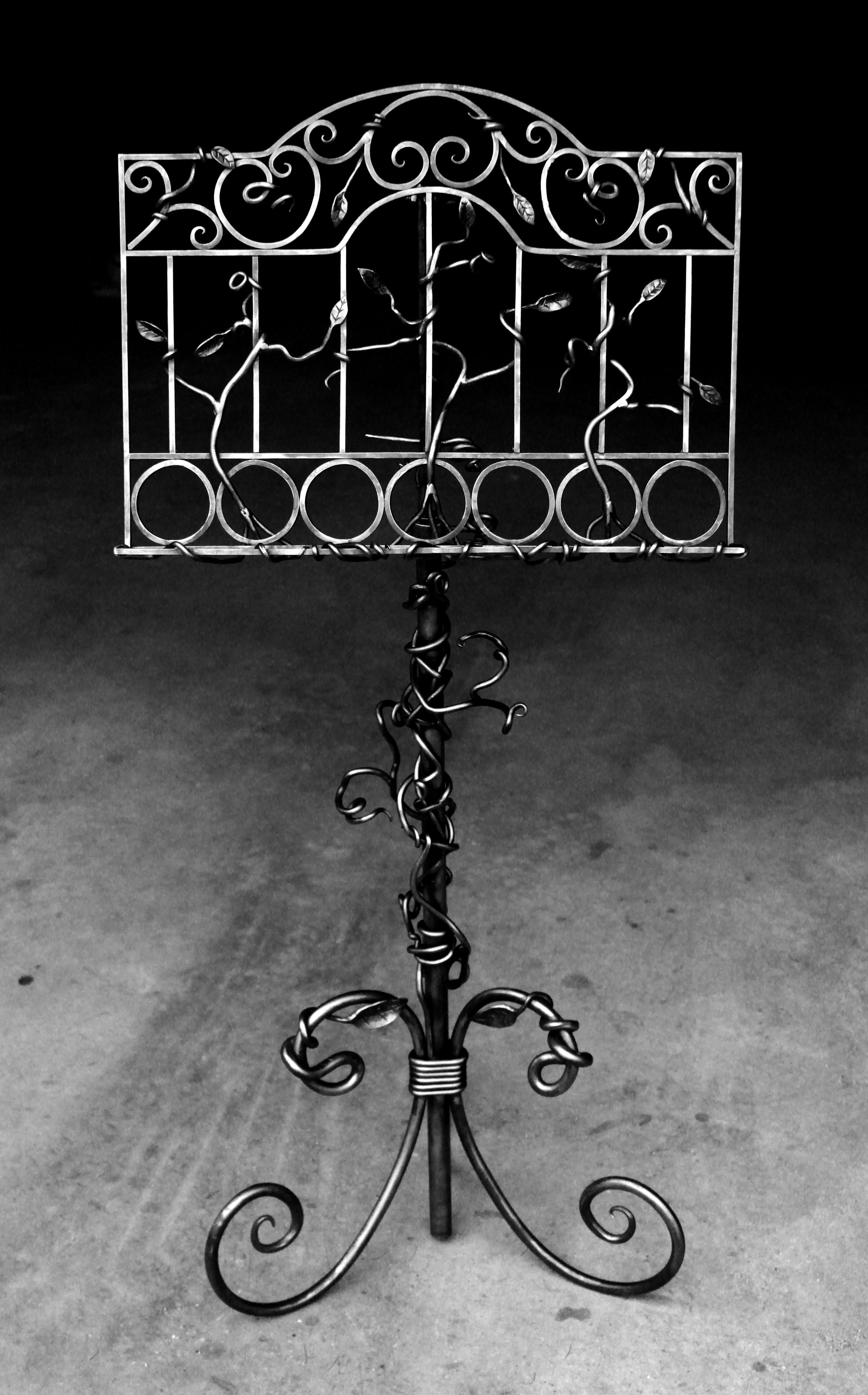

It’s okay, I get it. I know I have a problem. But try to understand it from my perspective. I make shit. I see a tool and I see its history and its story and it potential and I start to drool. I think about what I could make with it and how many things it has been used to make already and how well it was made and on and on. I see beauty in process, art in the act of creation and not just the creation itself. We talk about fine art. I want garage art.

Nick Moreau is an artist blacksmith and big fan of hand-pulled noodles. For recreation, he enjoys putzing around and watching 'Star Trek.' His business is Wicks Forge.